Science Snapshot - Gene Therapy Delivery to the Brain

Author: Michael Dryzer, PhD

Editor: Gabrielle Rushing, PhD, CSNK2A1 Foundation Chief Scientific Officer

CSNK2A1 Foundation Parent Advisory Board Reviewers: Connie Johnson, Katie Keiser

Gene therapy has been gaining traction in recent years as more treatments become available for previously incurable diseases affecting various parts of the body, including the

central nervous system (CNS). Now, scientists are capable of designing therapies to treat the root genetic cause of diseases like sickle cell, spinal muscular atrophy, and more (see this

Science Snapshot article for more in depth information on the mechanisms for gene therapy). However, an ever-present issue in this field is the question of delivery, especially to the brain and spinal cord. Despite this difficulty, researchers have made significant breakthroughs in recent years that will allow them to deliver gene therapies along several avenues to the brain.

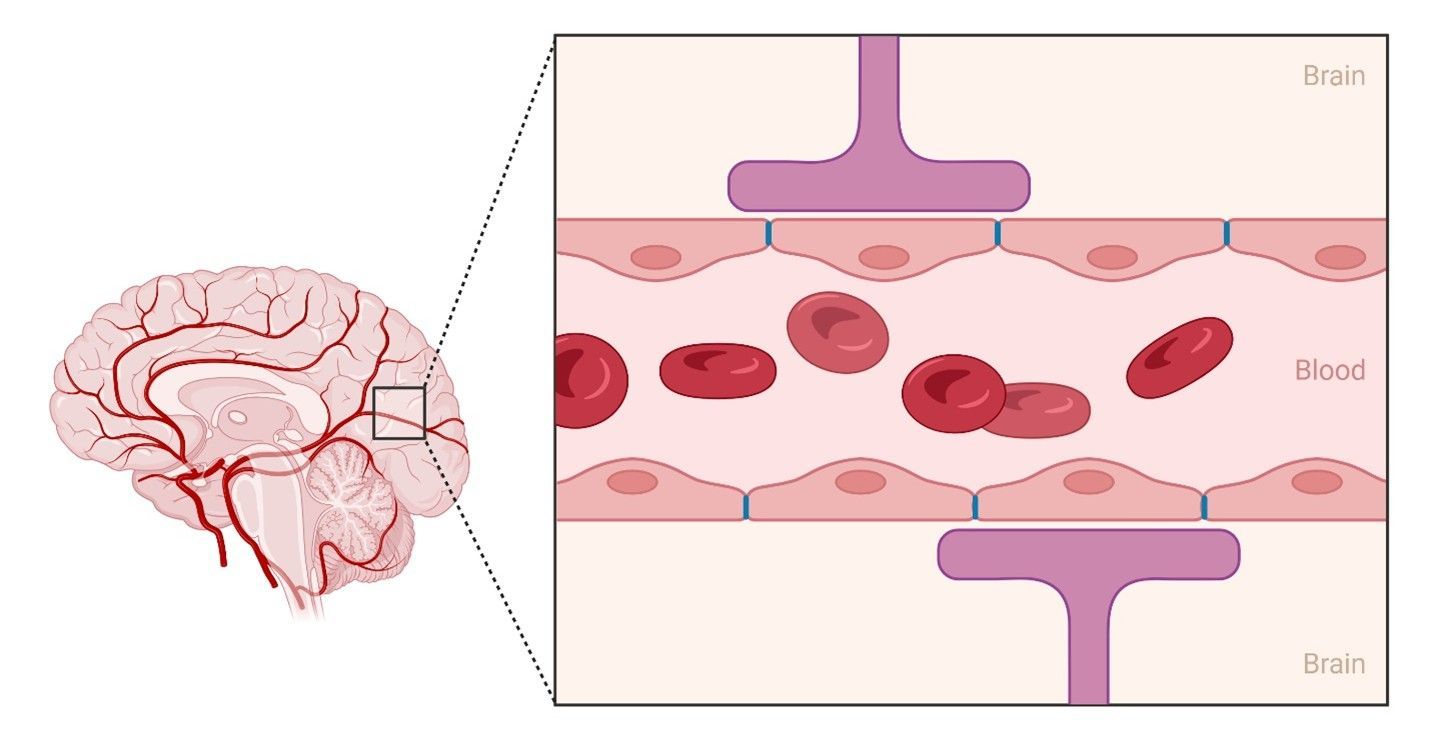

The Blood-brain Barrier: The Guardian of the Central Nervous System

The difficulty in administering gene therapies to the brain is due to a unique nervous system defense called the “blood-brain barrier” (BBB). The BBB is a shield made up of specialized cells surrounding all blood vessels that make contact with the brain. Its purpose is to restrict the movement of most substances from the blood to the brain. For the most part, this is advantageous; however, this does make it difficult to deliver

vectors, the microscopic carriers of gene therapies, to the brain where they can correct the genetic cause of disease. Fortunately, researchers working on ways to circumvent the BBB have discovered several promising methods of delivering gene therapy vectors to where they are needed.

Methods of Delivery

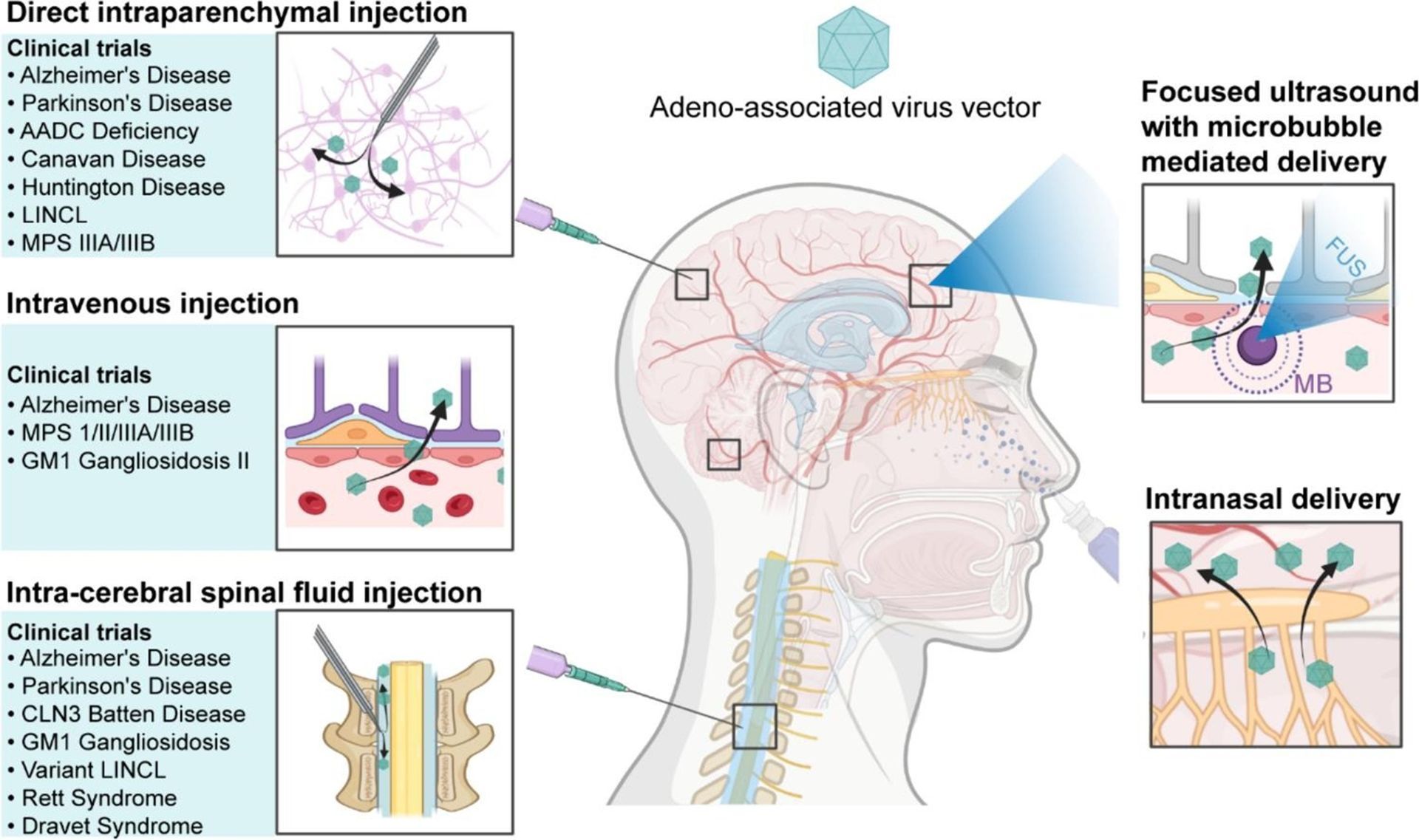

There are a variety of methods for gene therapy delivery to the brain, each of which comes with its own collection of advantages and disadvantages. Generally, the predominant methods can be divided into three categories: direct injection, intravenous injection, and intranasal delivery.

Direct injection

As its name implies, direct injection aims to deliver a given gene therapy directly to one of several parts of the CNS rather than through the blood or other pathways. This completely avoids the BBB, prevents blood-filtering organs like the spleen and liver from absorbing vectors before they reach their targets, and reduces the chance of the gene therapy unintentionally affecting other parts of the body. All direct injection methods involve opening a path to the CNS in order to inject the therapy with a needle. Currently, this is the most common method of delivery, but it also comes with the most risks and limitations.

Into the brain tissue

Of all the delivery methods mentioned in this article, intraparenchymal delivery is one of the most common methods currently being used in preclinical and clinical studies for treating brain diseases. For this method, a path for a needle is opened by boring a hole into the skull under which the target brain area is located. The needle can then be inserted through the hole into the brain tissue for direct delivery. Direct access to the brain is what makes this method simultaneously advantageous and dangerous. On one hand, direct access means it is possible to precisely target a particular brain region and use a lower therapeutic dose since the target region is readily available. On the other hand, an invasive surgical procedure such as this comes with the risk of infection, hemorrhaging, and loss of nerve cells at the injection sight (particularly if the dose is too high). Furthermore, this method can only influence the limited number of brain regions at or adjacent to the injection site; this is acceptable for conditions like Parkinson’s disease where the damage is at a specific location in the brain, and less so for conditions with more diffuse effects on the brain like Alzheimer’s disease and lysosomal storage diseases.

Into the cerebrospinal fluid

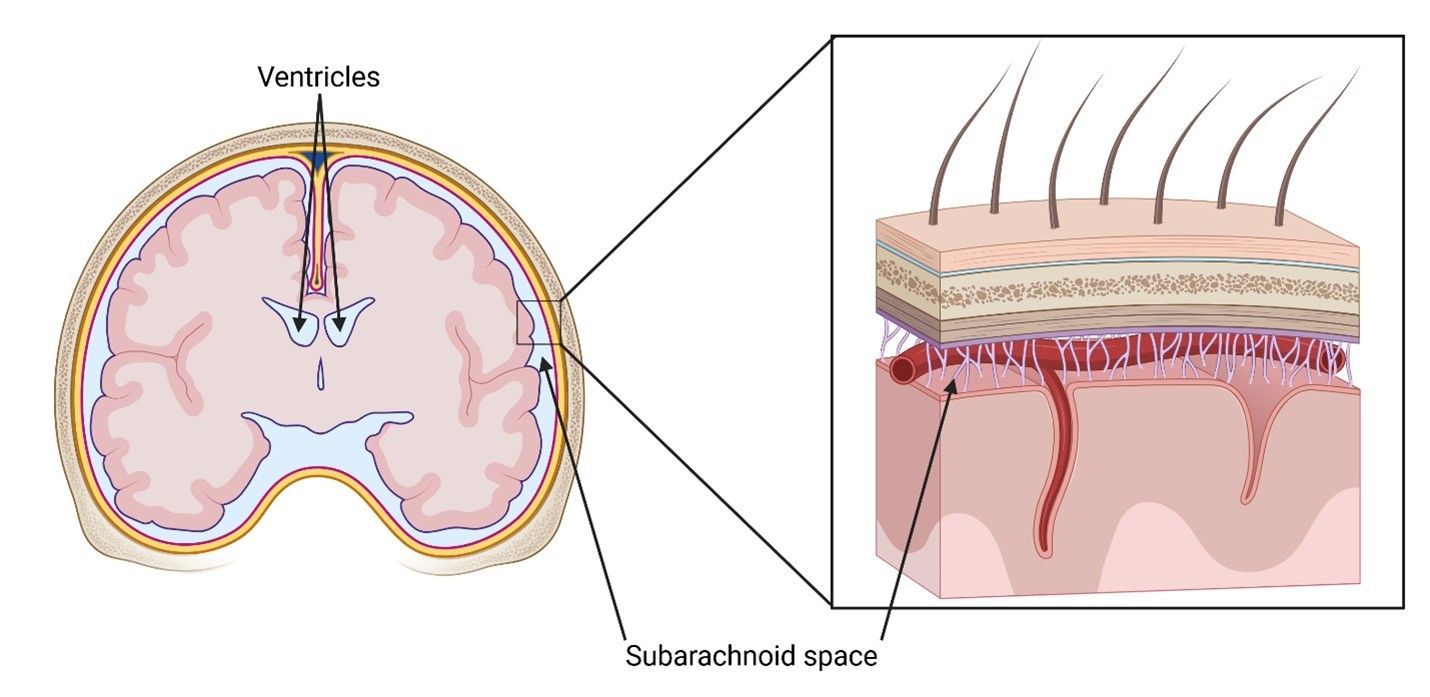

The other type of direct injection involves insertion into the

cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and can be split into three subtypes depending on the injection site: intracerebroventricular injection (ICV), intra-cistern magna injection (ICM), and intrathecal injection (IT). This method takes advantage of the fact that the brain and spinal cord are immersed in a special, nutrient-rich fluid called the CSF. The CSF circulates throughout the inside of the brain via chambers called ventricles

that are placed at specific locations to allow for efficient uptake by nerve cells. It also flows around the outside of the brain and spinal cord in a region called the subarachnoid space, which is enclosed between two of the three protective layers surrounding the CNS.

Each of the three subtypes of this method choose a different part of the CNS where the CSF flows as injection sites. ICV injects into the ventricles, the spaces located within different regions of the brain. ICM targets the subarachnoid space lying behind the cerebellum at the base of the brain and at the top of the spinal cord. IT disregards the brain altogether, instead injecting into the spinal cord’s subarachnoid space via a lumbar puncture at the base of the spine. Although the injection sites are different, the mechanisms of these methods are the same: after injection, the vector for the gene therapy is carried by the flow of the CSF to the rest of the CNS where it can deliver its cargo.

Like the intraparenchymal method, the three CSF injection methods bypass the BBB. But unlike the intraparenchymal method, the CSF methods take advantage of the CSF’s access to the spinal cord and brain, allowing for delivery to more regions beyond the injection site. However, these methods also come with their disadvantages. For ICV and ICM, surgical procedures are still required to grant access through the skull to the injection sites. Also, while the CSF flows to many parts of the brain, some of the more inaccessible parts deeper inside the brain remain untouched. Finally, the CSF provides its own set of challenges: while not being as restrictive as the BBB, the ependymal barrier that sits between the CSF and the brain can block vectors from entering brain tissue. Furthermore, the CSF is constantly being circulated and cleared from the CNS, so any vectors that don’t reach their targets in time are flushed away.

Intravenous injection

The methods mentioned above are the most common and effective ways we have today to deliver gene therapies to the brain, but they come with high risk and can result in harmful outcomes. Fortunately, researchers are developing more effective and safer processes for gene therapy delivery. Intravenous (IV) injection is a much safer method by which a therapy is injected into the bloodstream (via a vein in the arm for example), which carries it to the blood vessels supplying the CNS. To get around the BBB, scientists have come up with ways to alter the vector or the BBB itself to allow the passage of the therapeutic agents.

Using engineered vectors

There are a variety of vectors capable of carrying a gene therapy and moving to a specific location in the body for delivery. The most popular vector right now is a viral vector called an adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector. With our current knowledge of how genes work, scientists have removed the part of the genetic code in the AAV that tells it to “make virus” and replaced it with snippets of code containing a gene therapy and instructions for where to go in the body. Until recently, scientists had to rely on finding naturally occurring AAVs (like a type of AAV called AAV9) that were already capable of passing through the BBB. But now, by modifying the viral shell of an AAV, they’re able to develop new AAVs readily able to pass through the BBB.

In lieu of using viral vectors like AAVs, scientists have developed other types of vectors that serve the same purpose. A new kind of vector being developed is the lipid nanoparticle (LNP), a very small sphere made up of lipids, the same fatty material that normally encases our cells. Like a viral vector, genetic code for a gene therapy can be inserted into an LNP for delivery. Also, the fatty shell of the LNP can be modified with markers that enable it to cross the BBB and only interact with certain types of cells. LNPs can be injected intravenously where they will travel to the brain and be taken up by the target brain cells. Upon doing so, the genetic cargo is released into the cell where it will modify existing genetic code and correct any errors.

Using focused ultrasound

Besides modifying the vector, another way to get an intravenously injected vector past the BBB is to change the permeability of the BBB itself. There is ongoing research studying how focused ultrasound in combination with microbubbles can open the BBB to let a vector pass into the CNS. Ultrasound is the same technology used to image fetuses as they grow in the womb; it involves using high-frequency sound waves (higher than our ears can pick up) to noninvasively and safely deliver energy through the skull to the underlying brain tissue. Microbubbles are microscopic bubbles of gas that can be injected intravenously alongside a vector. Once both are carried to the BBB, the microbubbles are collapsed with focused ultrasound; this causes the BBB to temporarily become more permeable, allowing for the transfer of vectors into the brain.

Both IV methods come with a unique set of advantages and disadvantages. First, both methods are noninvasive and can be repeated. Because they are injected into the bloodstream, these approaches can circulate throughout the whole body (and later into the CNS) and are more suitable for conditions like ALS where both peripheral and CNS tissue need to be treated. Similarly, when it comes to the CNS itself, the diffuse nature of these methods allows for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease, Huntington’s disease, and other diseases that spread throughout the brain. Unfortunately, there are also disadvantages. Since the treatments are delivered intravenously, vectors run the risk of being absorbed by the liver and spleen or unintentionally releasing their cargo onto the wrong organs. Due to this, injections usually have higher dosages to make sure that at least some vectors reach their target, but this can cause problems with toxicity. For AAVs, their viral nature might provoke an immune response, which could compromise the ability of the vector to deliver the gene therapy. Furthermore, most people have already been exposed to AAV, so their immune systems might have antibodies that can neutralize AAV vectors, preventing them from reaching the brain and delivering their cargo. Notably, this applies to LNPs as well; although they are not made of virus, they can be recognized as foreign agents by the body and can provoke an immune response.

Intranasal delivery

The final method of note is the intranasal delivery of gene therapy. This approach exploits the fact that two parts of the brain, the optic nerves in the eyes and the olfactory nerve in the nose, are exposed to the external world. A vector can be sprayed into the nose, where it can travel up to the olfactory nerve and into the brain. This is a desirable method as it is noninvasive like the IV methods, easy to perform, and can be done repeatedly, even by the patients themselves, to increase delivery amounts. There are also some issues with this method. First, only a limited volume of material can be administered through the nose each time. Second, the vector might inadvertently affect nerves along the delivery pathway into the brain. Third, this method could be compromised by disease conditions like upper respiratory tract infections. Finally, researchers are uncertain of whether both the vector and the gene product can enter the brain via the olfactory nerve; right now, it seems like only the vector can proceed while the gene therapy is left behind in the olfactory nerve.

Future Directions

These are the prominent methods being used and researched at this time. Each has its own set of pros and cons that make it better or worse at treating certain conditions. Yet, researchers are working to improve methods for therapeutic delivery. For example, to prevent delivery to the wrong organs, brain-specific identifiers are being added to vectors like the AAV to ensure that its cargo can only be taken up and released in the brain. Also, for the direct injection methods, new imaging techniques including real-time imaging of the brain are being used to make sure the right injection sites are being targeted. Widespread adoption of gene therapy for all brain diseases is still far from being realized, but advances are being made every day. It will soon be possible to finally cure many of the diseases previously thought to be untouchable.

Author Bio

Michael Dryzer is a postdoctoral researcher at Johns Hopkins University where he completed his PhD in Biomedical Engineering. As a graduate student, Michael studied how fatigue and disease influence how humans make decisions about effort and reward. Currently, he is investigating the effectiveness of low-dose ketamine infusions to alleviate fatigue symptoms in patients with multiple sclerosis. Outside of the lab, Michael enjoys reading science fiction, playing video games, and being outdoors.

Glossary

Adeno-associated virus: Small viruses that infect humans and can be modified to deliver gene therapies

Blood-brain barrier: A highly selective semi-permeable membrane that separates the blood in the circulatory system from the brain

Central nervous system: A subsection of the human nervous system that is composed of the brain and spinal cord and manages functions like thought, memory, and reflexes

Cerebrospinal fluid: A clear, colorless fluid that circulates around the brain and spinal cord, providing protection and nourishment

Focused ultrasound: A non-invasive medical procedure that uses high-intensity ultrasound waves to target and treat specific tissues deep within the body

Lipid nanoparticles: Very small spherical particles composed of fatty lipids made to deliver drugs and gene therapies

Vector: A delivery system in the form of a virus or small particle that contains genetic information and can transport it to the inside of a cell

Ventricle: One of the four connected fluid-filled cavities located in the brain

References:

Viveros, A. (2022, November 22). Gene-delivering viruses reach the brain in a step toward gene therapy for neurological diseases. Broad Insitute. https://www.broadinstitute.org/news/gene-delivering-viruses-reach-brain-step-toward-gene-therapy-neurological-diseases.

Lee, Y., Jeong, M., Park, J., Jung, H., & Lee, H. (2023, October 2) Immunogenicity of lipid nanoparticles and its impact on the efficacy of mRNA vaccines and therapeutics. Experimental & Molecular Medicine. 55: 2085-2096. https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-023-01086-x.

DiCorato, A. (2024, May 16). New gene delivery vehicle shows promised for human brain gene therapy. Broad Institute. https://www.broadinstitute.org/news/new-gene-delivery-vehicle-shows-promise-human-brain-gene-therapy.

Ye, D., Chukwu, C., Yang, Y., Hu, Z., & Chen, H. (2024, August) Adeno-associated virus vector delivery to the brain: Technology advancements and clinical applications. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 211: 115363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2024.115363.

National Ataxia Foundation. (2024, September 5). All about gene therapy [Video file]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rqqTemH-1XQ&t=537s.

Wang, C., Xue, Y., Markovic, T., Li, H., Wang, S., Zhong, Y., Du, S., Zhang, Y., Hou, X., Yu, Y., Liu, Z., Tian, M., Kang, D.D., Wang, L., Guo, K., Cao, D., Yan, J., Deng, B., McComb, D.W., … , Dong, Y. (2025) Blood-brain-barrier-crossing lipid nanoparticles for mRNA delivery to the central nervous system. Nature Materials. 24: 1653-1663. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-024-02114-5.